scale-tone

My favourite catastrophic failures. №2. Toxic finalizers.

I believe, the misunderstanding started with this best practice, describing the preferred way of implementing IDisposable interface. Originally, in its most generic form it looked like this:

class BaseClass : IDisposable

{

// Flag: Has Dispose already been called?

bool disposed = false;

// Public implementation of Dispose pattern callable by consumers.

public void Dispose()

{

Dispose(true);

GC.SuppressFinalize(this);

}

// Protected implementation of Dispose pattern.

protected virtual void Dispose(bool disposing)

{

if (disposed)

return;

if (disposing)

{

// Free any other managed objects here.

//

}

// Free any unmanaged objects here.

//

disposed = true;

}

~BaseClass()

{

Dispose(false);

}

}

And as the most generic form, this implementation makes perfect sense. The authors just wanted to cover all possible cases, specifically, cases when your BaseClass directly aggregates some unmanaged resources and when your derived classes might directly aggregate some unmanaged resources. The keywords here are “directly aggregates” (that is, contains a field, that holds a reference to) and “unmanaged resource”.

The fact is though, that in modern .Net world the chance that you would need to directly manipulate unmanaged resources is extremely rare. Unless you are yourself coding the .Net Framework or you are making a wrapper around some C++ AI library, you just aren’t gonna need it. So, in 99.(9)% of cases, in the above code disposing will be always equal to true, there will be no unmanaged objects to free, and therefore the finalizer will not be needed.

Ironically, by looking at the above code, so many .Net developers in the world started thinking that a finalizer is essential for properly implementing IDisposable. And although the today’s version of Disposable pattern clearly discourages making types finalizable, people still keep copypasting that sample and peppering their codebase with unneeded tildes (“~”).

Now, here are three reasons why you should avoid using finalizers in your .Net code (for exceptions go to the end):

- They are useless.

- They are harmful.

- They are dangerous.

1. Finalizers are useless.

As we all know, .Net provides us with the luxury of automatic memory management. The only reason for introducing finalizers (destructors in C++ terminology) was to allow .Net developers to work with unmanaged resources (e.g. Win32 handles). If you don’t - you’ll be really struggling to find a good use for them (see the exceptions at the end). Moreover, by default you won’t be able to access unmanaged resources in your .Net project - you’ll need to explicitly enable that with AllowUnsafeBlocks switch. So, if a .Net project has some finalizable classes in it and doesn’t have that flag set on - that is already quite suspicious.

2. Finalizers are harmful.

As described by Chris Brumme, Eric Lippert and others, finalizable objects are much more expensive. Their creation is slower and they live longer. Actually, the whole graph of objects reachable from a finalizable object will survive the first GC. In other words, each finalizer in your code increases your app’s memory footprint and might increase it significantly. Also, depending on what actually happens in your finalizer, the performance might as well suffer significantly. Worst case is a deadlock inside it: in that case your app will quickly (but not instantly!) die of OutOfMemoryException.

3. Finalizers are dangerous.

3.1. Because their order of execution is unpredictable.

The below sample is distilled from one of the projects I was taking part in.

Let’s say you have yourself a third-party managed wrapper library, that internally handles some unmanaged resource. Let’s model the behavior of that unmanaged resource like this:

class UnderlyingResource

{

private bool isFreed;

public void Free()

{

if (this.isFreed)

{

throw new ObjectDisposedException(nameof(UnderlyingResource));

}

this.isFreed = true;

}

}

Essentially, it has some method for freeing itself, and that method isn’t idempotent. Now, because the developer of that third-party library always follows all the best practices, the code of it would look like this:

class TheirFinalizableClass : IDisposable

{

private readonly UnderlyingResource resource = new UnderlyingResource();

~TheirFinalizableClass()

{

this.resource.Free();

}

public void Dispose()

{

this.resource.Free();

GC.SuppressFinalize(this);

}

}

Note that the IDisposable pattern is implemented almost correctly - except for that it doesn’t prevent the underlying resource from being released twice.

Now you choose to use that library in your code. But because you’re a very senior developer, you always ensure that all the resources are properly disposed (even if your component is misused by others), and this prompts you to have a finalizer in your class as well:

class MyFinalizableClass

{

private readonly TheirFinalizableClass theirClass = new TheirFinalizableClass();

~MyFinalizableClass()

{

this.theirClass.Dispose();

}

}

Now let’s test it:

static void Main(string[] args)

{

try

{

var c = new MyFinalizableClass();

}

catch (Exception e)

{

// We never get here in case of an exception inside a finalizer!

Console.WriteLine("Error: " + e);

}

}

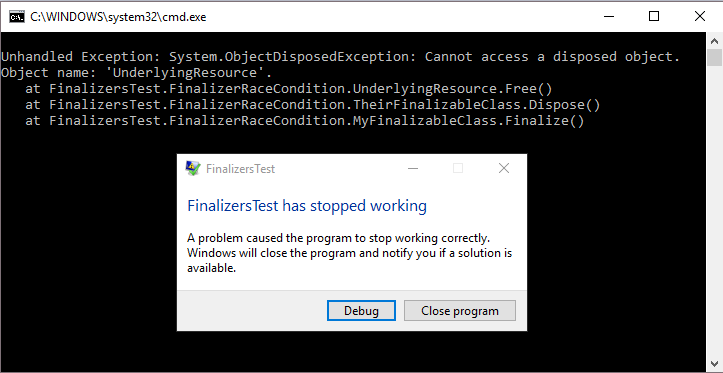

Oops, the program crashes with ObjectDisposedException:

Why did that happen? Exactly: because the finalizers of MyFinalizableClass and TheirFinalizableClass are executed in unpredictable order, and in this particular case TheirFinalizableClass was the first one. The worst thing about it is that this behavior is flaky: depending on .Net version being used, on the build configuration, on the exact place in the code or on the current Moon phase one finalizer can defeat the other. And you will only see your service crashing in arbitrary moments of time in production.

3.2. Because their moment of execution is unpredictable.

And this sample is a purified version of a bug that actually existed for quite a long time in some client SDK of some very well-known vendor.

There was one senior developer, who for some reason decided to write his own implementation of a Stream, which looked like that:

class MyStream : FileStream

{

private bool isDisposed;

public MyStream(string path) : base(path, FileMode.Open, FileAccess.Read)

{

}

protected override void Dispose(bool disposing)

{

// intentionally not idempotent

if (this.isDisposed)

{

throw new ObjectDisposedException(nameof(MyStream));

}

this.isDisposed = true;

base.Dispose(disposing);

}

}

Note that, again, there’s almost nothing wrong with it except that the Dispose() method isn’t idempotent.

Then, there was another senior developer, who was using MyStream in the following way:

class MyStreamAggregator : IDisposable

{

public Stream UnderlyingStream { get; }

public MyStreamAggregator()

{

this.UnderlyingStream = new MyStream(@"c:\temp\test.png");

}

~MyStreamAggregator()

{

try

{

this.Dispose(false);

}

catch (Exception)

{

// do nothing

}

}

public void Dispose()

{

this.Dispose(true);

GC.SuppressFinalize(this);

}

private void Dispose(bool disposing)

{

if (disposing)

{

// dispose managed resources

}

// BUG: this should be _inside_ the if block!

this.UnderlyingStream.Dispose();

}

}

Note that IDisposable pattern is again implemented almost correctly: this time there’s even a try-catch inside the finalizer (the author probably heard something about unpredictable order of execution and troubles it might cause). The only strange design decision here is to expose the UnderlyingStream to the public (normally you either keep your aggregated streams private or you don’t aggregate them).

Now let’s emulate the behavior of this code in production (that’s how it was written and that’s how it really behaved, I’m not lying):

static void Main(string[] args)

{

var agg = new MyStreamAggregator();

using (var stream = agg.UnderlyingStream)

{

while (stream.Position != stream.Length)

{

// Emulate garbage collection occuring exactly at this place

if (stream.Position == 123)

{

GC.Collect(); GC.WaitForPendingFinalizers();

}

stream.ReadByte();

}

}

}

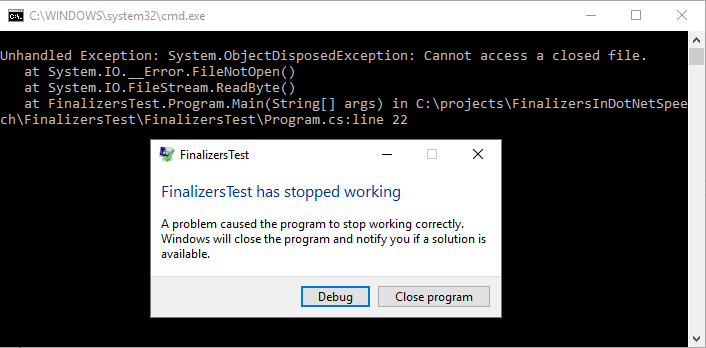

Run this code in Debug configuration. It finishes successfully. Now run it in Release configuration. Oops, the program crashes with ObjectDisposedException:

Why did it happen this time? Well, we force the garbage collection to be executed while the underlying stream is still being enumerated. That garbage collection causes MyStreamAggregator’s finalizer to be executed and the stream to be closed. Next attempt to read from it fails with ObjectDisposedException, which we can see on the screen. Why doesn’t it throw in Debug mode (or, better to ask, why that senior developer didn’t notice such a nasty bug in his code during testing)? It’s because in Debug mode no optimizations are made by the compiler, and the agg variable is considered alive until the end of the method. While in Release mode the compiler notices that agg variable is not being used (it’s agg.UnderlyingStream, that’s being used, not agg itself) and leaves the MyStreamAggregator instance at garbage collector’s disposal. During real service’s lifetime garbage collections occur at arbitrary moments of time, therefore such crashes look absolutely random and mysterious to you. Until you look at the sources.

As you can imagine, spooky bugs like that - only noticeable in production, at random times, with no any consistent pattern - are the the worst kind of bugs to investigate. Yet so easy to avoid them: just don’t use finalizers!

Or, in more generic form: please, don’t blindly follow all the best practices. Think them over first!

Exceptions to the rule.

- Well, obviously, if you do mess around with truly unmanaged resources, then you are required to free them in your finalizer.

- When you write some monitoring/logging library and you want to ensure that some collected data is dumped to the storage even if your consumer forgot to use using() or call Dispose().

- If you’re Jeffrey Richter’s fan and you believe in Object Immortality (Please, don’t! I mean, it’s fine to be Jeffrey Richter’s fan, but it’s not fine to use object resurrection).